Moe is a controversial word.

Generally used by both Western and Eastern subculture fans to refer to something they find cute or adorable in any given medium of subculture, it is a concept that is actually seldom rendered in the written language. In the real world, fundamentally explaining what it exactly is and what it encompasses goes beyond the word’s grammatical usage and definition in Japanese. How it exists may not be visual or even auditory. It’s all about practicality. Execution.

A girl hurrying up on her way to school in the morning while holding a piece of bread in her mouth is a classic but almost cliché moe situation by now. Perhaps, others might prefer being woken up by your loli upbeat childhood friend on a certain summer day.

I know what you’re thinking. Some of you might be wondering if this is even a serious post and let me tell you it totally is.

Moe is serious business. And as much as it pains me to say it, it’s not understood that well by certain communities and fans. Moe works in a way that is unconsciously connected to what people might yearn for. There is that “spark” that ignites a fire in those who find a given situation, character, visual gag, phrase, or execution of any of the aforementioned elements great. This set of elements are present in anime, manga, light novels, eroge, and video games and are instantly recognized by fans. These symbols that have seeped in the subconscious through familiarity and exposition to subculture through the years. We recognize them by heart (あの女のハウス, 南の島), just like most folks do with the golden arches in McDonalds. It’s not just a concept to address the plain cute. It goes way beyond that, so much that it’s why this is so difficult to convert into words.

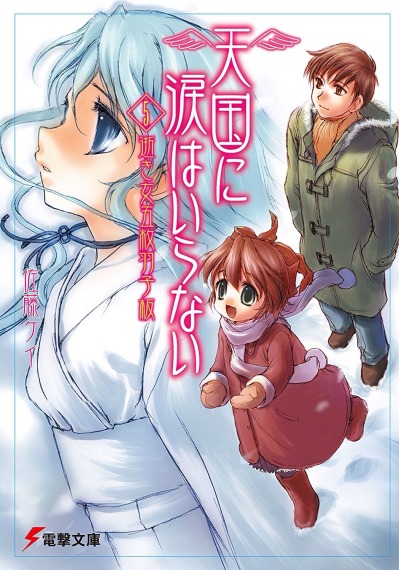

Tengoku ni Namida wa Iranai is a LN series capable of conveying the intricacies of the moe concept. Defined by its fans as meta-moe, it examines why these tropes are riveting.

Koreo is a high-school student descendant of a family that holds spectral powers, and makes a living using them. Divination, exorcism, or just whatever odd jobs customers have for him usual institutions can’t deal with.

He ends up having to summon a Seraphim to free an allegedly cursed classroom in school, but he notices things are growing out of control. A Seraphim is said to be the closest angel to God in the angelical order and he is the most loyal in the Christian religion. Its name is Abdiel and with his help, Koreo solves the case and tracks down the curse’s cause: a girl at school named Tama who turns out to be a devil. And a loli one at that. She later becomes the series’ main heroine.

But to Koreo’s dismay, Abdiel turns out to be a full-fledged lolicon with no interest whatsoever in any other type of girl, and immediately fixes his eye on Tama. So Koreo spends most of the series’ length protecting Tama’s chastity from Abdiel. Abdiel’s only saving grace: He is super handsome —an ikemen— so he has no trouble to get girls to pay attention to him.

Here’s where the author totally caught me off guard. That duo, Koreo and Abdiel, deliver on every single emotional, narrative, and even creative aspect throughout the 12-long-volume series.

The author knows fully well what roles the characters represent. Koreo is a pseudo protagonist for he is in charge of rebutting. A tsukkomi character basically. Whatever crap Abdiel spits out when they encounter with a cute girl, Koreo retaliates with a zinger. But Abdiel replies with sense of humor and full command of the Japanese language about what he is preaching about. So he argues about why he is right and why lolis are the truth of the universe. And what’s the most amazing about it: Abdiel almost convinces you every time about his stance!

Moe is always at the center of the discussion. Abdiel is trying to teach Koreo the art of it, how to fully appreciate it, and what it’s so fascinating to him about it. However, Koreo sees Abdiel’s speeches as nothing but pedophiles’ rationalizations. Abdiel’s obsessed with bishoujos, and the concept of what the ideal loli bishoujo is always has Koreo (the reason) and Abdiel (the passion) ending up in a heated discussion.

One would think the moe concept is related to the human libido in an unconscious way, but it isn’t. Moe is not about eroticism. In Abdiel’s words, moe is finding passion and a sense of worship that you find beautiful in subculture. Moe can be a little girl wearing glasses that are about to fall while saying ‘Ehehe’. Moe can be a tank storming through a building while firing non-stop. Moe can be a painting on the wall. Eating choco-chips ice cream in a sunny day. And for him, the peak of moe is loli bishoujo, his God and religion. If watching a flower grow is super moe to someone and it causes that person a boner, who are we to judge?

There’s a reason why in the subculture realm there are military otaku, cards games otaku, arcade otaku and so on.

Each of these communities find a different type of moe in their activities, perhaps different to the manga or anime ones. A rhythm game otaku may not go nuts over a busty loli, but he will go apeshit upon dancing to the rhythm of Miku in an arcade!

To discuss more in depth about the concept, we need to know more about the word and its meaning, even if only on paper. Here’s when comes into play how the word can work in Japanese language and in what situations it is usually put to use, at least in an idiomatic, slangy way:

- 燃え is what you usually find passionate and exciting to the point it makes your blood boil. It usually, but not exclusively, refers to a situation or the circumstances of said situation.

- 萌え works in a different array of situations and is more ambiguous in Japanese. It usually has a more visual side to it, but it’s not strictly used in a visual context. Tenderness and endearment are often at the heart of it. The word can also point out the execution of certain situations or phrases said by a character. It has a different nature to the previous form and its original meaning is barely put to use in modern Japanese.

One of the reasons why the word’s vagueness has spread across Western communities is because there is no way to emphasize the difference in usage between both forms. And the difference is crucial as pointed out by Abdiel countless times throughout the series.

燃え example:

You can fantasize about the qualities of an heroine — Let’s assume you like the oneesan-type of girl. That girl must be a little bossy, but also gentle, and whenever you do something right she gives you a pat on your head while saying いい子いい子… which makes your blood boil out of excitement! Just from imagining that in your head you’re 燃えing! This is just one of countless of examples, but as you can see, what’s being valored here is the execution of the elements or situation. There are people who find exciting putting themselves in danger, and they 燃える in those situations as well. A mixture of passion and excitement, so to speak.

萌え example:

Now, the 萌え can be related to cute things, yes. But is not exactly propelled by excitement or cuteness, but by a feeling of tenderness and adoration towards a situation, or element (character, setting, etc). When you read, watch, or hear a set of elements put together — and that causes you tickles, makes you grin out of nowhere, or simply moves you, you’re 萌えing without even realizing it.

With this set of elements put together, let’s use this situation:

Two female high school students are about to go home. We’ll call them Tonoko —blue-haired, and gentle. And Sumika — red-haired, and with a serious expression, but kind at heart. They’re the last students in the classroom since they’re on cleaning duty, and earnestly do it as the red-tinged sunset shines through the windows. They’ve been friends since childhood, however, in the last couple of months they have showed an affection for each other that perhaps goes beyond what can be called friendship. Is it the age, or perhaps the passing of time what has created this change in their relationship? It remains a mystery, but what it’s certain is that they no longer look at each other as mere “friends,” but not as something else either.

Soon enough they finish cleaning, and as Tonoko is about to leave the classroom, Sumika says: 待って! to which Tonoko reacts just by stopping right before the door, but doesn’t turn around. You can hear her heavy breathing. Sumika walks to her and… hugs her, placing her arms around Tonoko’s neck, gently caressing her collar bones with the tip of her fingers.

Suddenly, Sumika whispers in Tonoko’s ear: 行かないで… in an almost subdued, tear-choked voice. Tonoko’s cheeks turn to a reddish, almost peachy color. Tonoko turns around, and says to Sumika’s face while kissing her right cheek: 安心して, どこにも行かないから… And then they gently kiss.

This is an almost perfect embodiment of 萌え, and perhaps you were 萌えing while reading it without noticing it! This is similar to an example given by Abdiel in the series, I just changed the girls’ names. As I mentioned earlier, this concept is propelled by a sense of intimacy, tenderness, and adoration, which said in a more general and simple term would be “cute.” Even if you’ve only read this situation, you can pretty much picture it in your mind!

This, however, doesn’t signify the vagueness of the word in Japanese communities. The “ideal” usage is nonexistent. I wouldn’t be exaggerating if I said there are still people who think the word moe and kawaii are interchangeable.

These sort of discussions happen countless times as the series progresses. As Koreo and Abdiel encounter with new heroines in each volume, a new element to the discussion is added. You do nothing but be in awe at how clever and knowledgeable the author is as you can tell he is a fan-to-the-bone of all of this and how everything speaks volumes to the reader.

Each volume has a heroine that we are all familiar with: A nekomimi girl, a shrine maiden, a childhood friend character, a mahou shoujo character, the oneesan type character, and many more.

The duo encounters with different staple heroines of subculture throughout the series and help them out with their problems. And along the way, Koreo and Abdiel discuss about the properties of said heroines and what we fans find compelling about each of them. Most importantly, they are trying to discover what the true essence of each of them is.

Can a girl-with-glasses character (meganekko, 眼鏡っ娘) only be described as such when she’s exclusively wearing them? Isn’t the essence of a meganekko the gentle clumsy girl with her soft usage of language? Would it be a problem if she’s not actively wearing them? What about the nekomimi girl? Must she always wear a pair of cat’s ears? Wouldn’t meowing and imitating cats be enough to qualify as that character? Let the discussion begin!

Every book explores a heroine in a different fashion by the duo, while having great scenes of comedy, as well as poignant and touching moments with our beloved heroines who always hit so close to home.

They’re almost religious symbols who not only appear in this light novel series but everywhere in subculture. We share with these characters deeply intimate moments on a daily basis.

This is the reason why the series is defined as meta-moe: it speaks so much to the reader and other subculture fans you can’t help but feel the author is directly addressing you. Maybe it’s telling that even the characters themselves break the fourth wall.

Another aspect the series excels at is not only characterization, but also knowledge usually involving Western theology, the divine, Japanese literature, and the occult.

The subtitle of each volume is usually both a kanji pun and an allegory to ancient literature (legends or folktales) spread across Japan throughout the ages.

Examples:

- Subtitle in vol 4. is 男色一代男 and it’s a play on words on the era-defining Edo work 好色一代男, which deals with eroticism and the unquenchable libido and desire a man can hold for women. However, the author of Tengoku does the complete opposite in vol 4. and displays the mystique of eroticism towards men as well as using homosexual characters.

- In vol. 5, the subtitle 逝き女(ゆきおんな) is a play on words on the legend of the youkai 雪女, as well as an allegory to the short-story by Lafcadio Hearn (a.k.a. the most Japanese Westerner ever). In both stories snow, grief, and loss are the recurrent themes (the heroine of this volume dies).

And the list goes on. Not only does the author show an immeasurable love for subculture, but also for literature, history theology, and the act of learning. He said his style has been called too “absurd,” to which he replied “I just write whatever I want to write; I maintain true to myself, and that’s the key to success. Perhaps not financially, but spiritually. I win either way in any case.”

Tengoku ni Namida wa Iranai is similar to the Monogatari series in the sense you are so attracted to the characters and their constant characterization, you want to seem them interact and have banter so bad. And along the way, they also offer a great opportunity to learn new things as well as giving you one hell of a time. So what’s more interesting to banter about than random knowledge, moe, subculture, and bishoujos?

In the end, moe is more than visual gags and cute characters, it’s about familiarity, intimacy, and passion towards any given element of subculture. You don’t see moe; you feel it.

So feel it.